Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a common condition that causes the level of sugar (glucose) in the blood to become too high. There are a number of factors that can affect the risk of developing T2D including: age, family history of T2D, ethnicity, high blood pressure and being overweight. Key lifestyle recommendations to reduce risk of T2D include maintaining a healthy bodyweight, eating a healthy, balanced diet that is high in fibre and low in saturated fat, free sugars and salt, and being physically active.

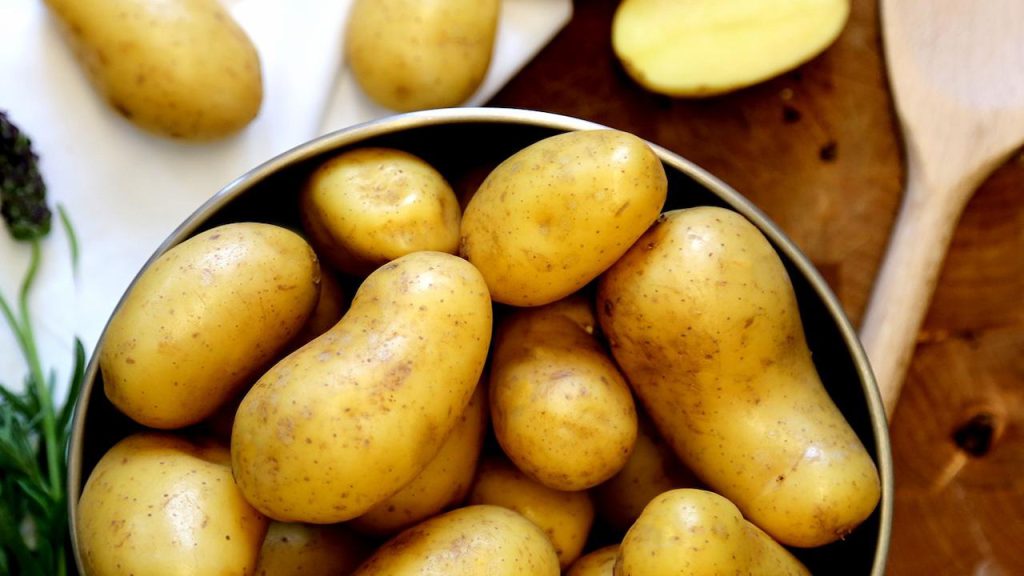

While potatoes have been an important dietary staple globally for hundreds of years, and are recommended as part of a healthy, balanced diet in national and international guidelines, an association between potato consumption and the risk of developing T2D has been reported. However, the evidence is inconsistent, with some studies reporting an association, some no association and some a lower risk of developing T2D with potato consumption. In this blog we take a brief look at the scientific evidence on potatoes and T2D risk and try to unravel what it can tell us…

What's the evidence on potatoes and type 2 diabetes risk?

There is some evidence from observational studies that intake of potatoes, particularly French fries (chips) is associated with increased risk of T2D (1-6). However, observational studies (where researchers just observe the effect of a risk factor rather than trying to change who is or isn’t exposed to it) can only show associations, not cause and effect, and it is not possible to exclude confounding by other variables. Importantly, differences in cooking methods (like frying) and what’s added at the table (e.g. added salt, fat or sauces) are not always taken into account in these studies. Eating fries is likely to be associated with other unhealthy behaviours, and these factors (rather than consumption of fries themselves) could influence any observed association between potato intake and health outcomes. For example, people who consume fries may also be less likely to eat a healthier diet overall, have a higher body weight, be more likely to smoke, drink alcohol and sugar sweetened beverages, and/or have lower physical activity levels. Such associations must therefore be interpreted with caution, and the evidence to date does not support a clear recommendation to reduce total potato intake, with the possible exception of regular consumption of fried chips.

We should also consider that potatoes are rarely eaten on their own and it is hard to fully capture the complexity of what we eat, especially over many years. Increasingly the importance of dietary patterns is recognised as important in health, rather than focussing on specific foods. Healthy dietary patterns higher in fibre, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and lower in refined grains, and sugar-sweetened foods and beverages, help reduce the risk of developing T2D7. The evidence perhaps suggests that frying potatoes are not the healthiest way to eat potatoes, and potatoes like other starchy carbohydrates, should be eaten in a healthy, balanced diet. If you choose to eat potatoes, try to opt for healthier options such as limiting deep-fried versions, serving them in skins, limiting addition of salt or sauces high in saturated fat, and boiling, baking, mashing or roasting with only a small amount of fat or oil8.

Like any other carbohydrate-containing food or drink, potatoes increase blood sugar levels. One of the mechanisms suggested to explain the association between potatoes and T2D risk, is therefore its glycaemic index (GI) (the measurement of how quickly glucose from carbohydrate-containing foods gets into the bloodstream after consumption). Potatoes can be a high GI food and a diet containing more foods that are higher in GI is associated with a greater risk of T2D. However, using GI only can be problematic, as it does not consider the portion size. The glycaemic load, that accounts for the amount of available carbohydrate in a portion, has been suggested as a better measure. This is because the amount of carbohydrate you eat has a bigger effect on blood glucose levels than GI alone. In addition, potatoes are typically eaten as part of a meal, and what they are combined with will change the glycaemic impact overall. For example, fat lowers the GI of a food and crisps will actually have a lower GI than potatoes cooked without fat. So a lower GI alone doesn’t necessarily determine whether a food is a healthy choice. If you do want to lower your GI then use new potatoes instead of old potatoes, or try sweet potatoes for a change9.

Overall message

Potatoes are included in dietary guidelines around the world and make a useful contribution to certain nutrient intakes.

Potatoes provide potassium and thiamin and contribute to fibre, vitamin C and vitamin B6 intakes of adults in the UK, but if you choose to eat potatoes, including skins will increase the fibre content and healthier cooking and preparation methods should be used.

It’s important to consider your overall dietary pattern rather than just focus singularly on the consumption of potatoes both for weight management and T2D risk. Eating a healthy, balanced diet, maintaining a healthy body weight and being physical activity are all important.

References

- Borch D et al. (2016) Potatoes and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: a systematic review of clinical intervention and observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 104(2): 489-98.

- Bidel Z et al. (2018) Potato consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: A dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 27: 86-91.

- Schwingshackl L et al. (2018) Potatoes and risk of chronic disease: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. [Epub ahead of print]

- Robertson TM et al. (2018) Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato. Nutrients. 10(11).

- Beals KA (2019) Potatoes, Nutrition and Health. Am. J. Potato Res. 96: 102–110

- Quan W, Jiao Y, Xue C et al. (2020) Processed potatoes intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine prospective cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 5:1-9.

- USDA (2021) Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Available at: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed 25 February 2021)

- NHS (2020) Starchy foods and carbohydrates. Available at: https://bit.ly/2WACprE (accessed 25 February 2021)

- Diabetes UK (2021) Glycaemic index and diabetes. Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/enjoy-food/carbohydrates-and-diabetes/glycaemic-index-and-diabetes (accessed 25 February 2021)

The British Nutrition Foundation has reviewed the accuracy of the scientific content of this page. Please note this does not include linked pages on June 2, 2021.

The British Nutrition Foundation is not a lobbying organisation nor does it endorse any products or engage in food advertising campaigns.

For more information about the British Nutrition Foundation, please visit www.nutrition.org.uk